Nurhafizah Hasim* & Nur Hidayah Ahmad

*Corresponding author: nurhafizah.h@utm.my

“Smart glass can contribute to a cleaner future by reducing microplastic pollution in several ways. Its use in buildings reduces energy consumption, which can indirectly lower the demand for plastic-related products and processes. Additionally, smart glass materials are often recyclable and have long lifespans, minimizing waste and the potential for microplastic generation.”

Dr. Nurhafizah Hasim is a member of Advanced Optical Materials Research Group (AOMRG) and a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Physics, Faculty of Science, UTM.

Introduction

Microplastics, tiny plastic fragments less than 5 mm in size, have emerged as a serious global pollutant. These particles result from the degradation of larger plastic items and are now commonly detected in oceans, rivers, soil, drinking water, and even within the human body. Their minute size allows them to evade traditional filtration systems and accumulate in aquatic food chains, posing significant threats to ecosystems and public health (Eerkes-Medrano et al., 2015). Given their persistence and the limitations of conventional remediation methods, there is a growing demand for smart materials that not only resist contamination but also actively eliminate it. One such promising material is a newly developed phosphate-based glass that integrates environmental functionality into its structure.

Material Design

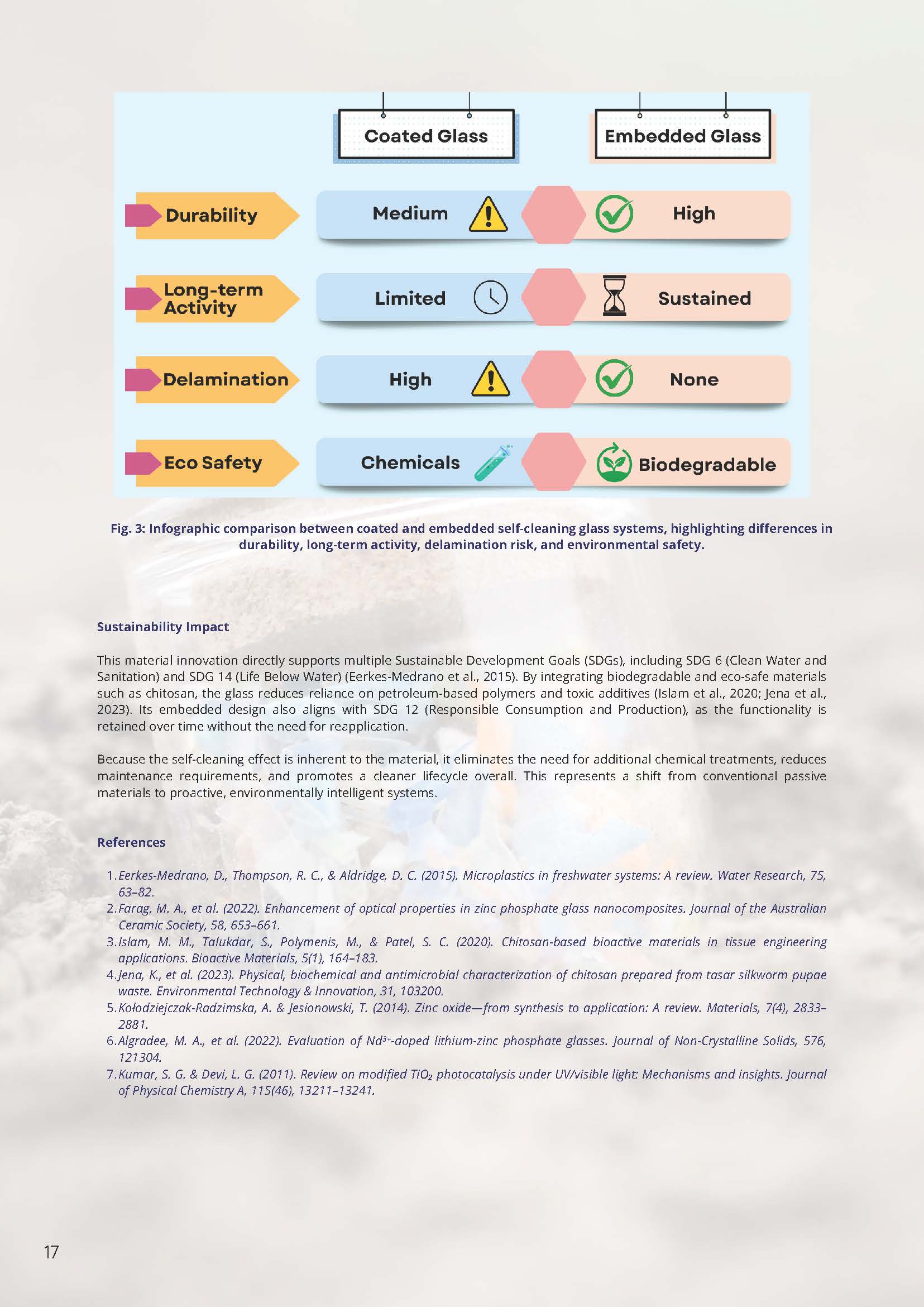

This novel glass system is synthesised using the melt-quenching method and consists of a phosphate-based matrix embedded with zinc oxide (ZnO) nanoparticles and chitosan. Phosphorus pentoxide (P₂O₅) serves as the glass former, while strontium oxide (SrO), lithium oxide (Li₂O), and ZnO function as modifiers to enhance the glass network and tailor its optical and thermal properties (Farag et al., 2022). What makes this material unique is that the functional agents, ZnO nanoparticles and chitosan, are not applied as surface coatings but are embedded directly into the glass matrix.

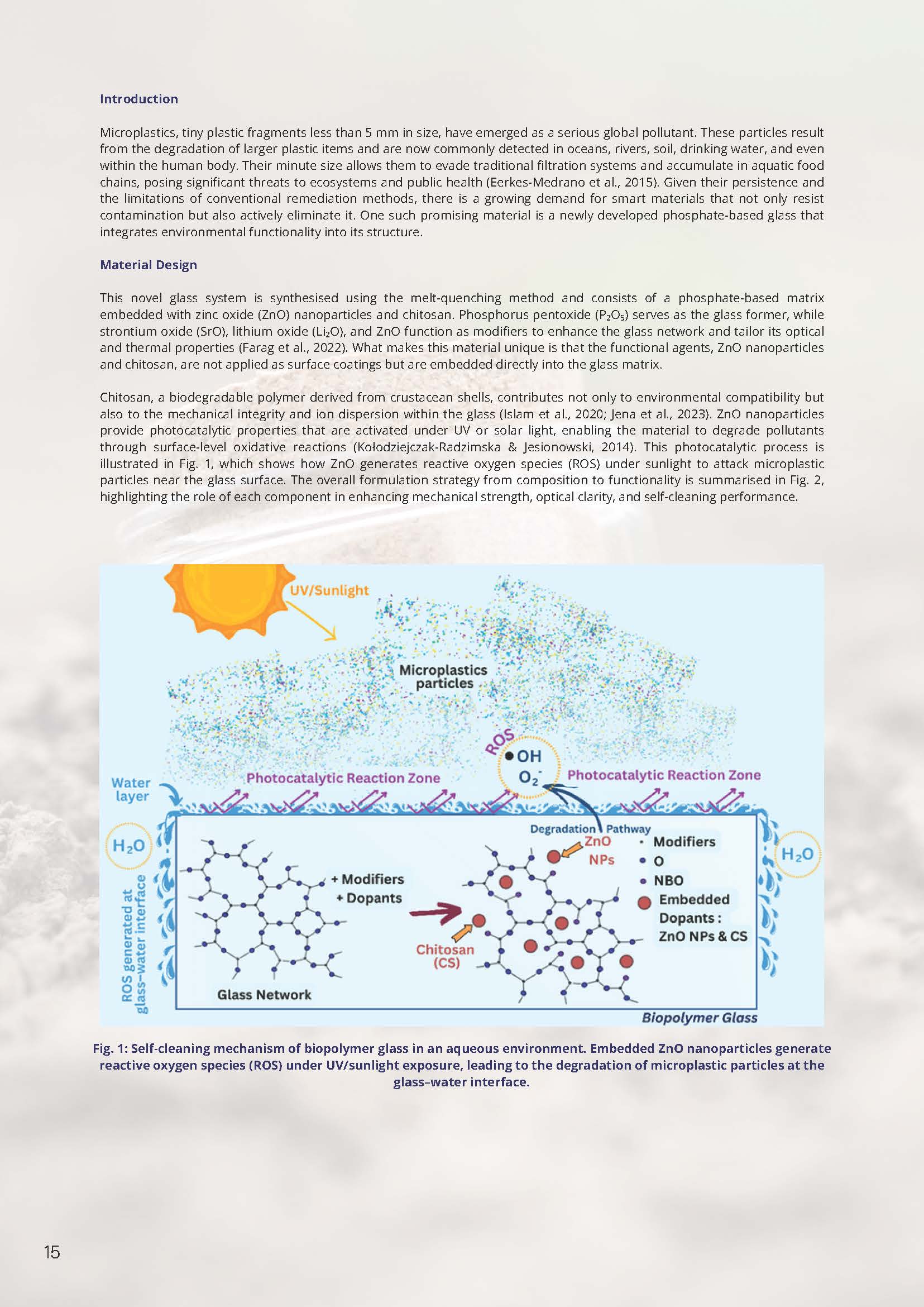

Chitosan, a biodegradable polymer derived from crustacean shells, contributes not only to environmental compatibility but also to the mechanical integrity and ion dispersion within the glass (Islam et al., 2020; Jena et al., 2023). ZnO nanoparticles provide photocatalytic properties that are activated under UV or solar light, enabling the material to degrade pollutants through surface-level oxidative reactions (Kołodziejczak-Radzimska & Jesionowski, 2014). This photocatalytic process is illustrated in Fig. 1, which shows how ZnO generates reactive oxygen species (ROS) under sunlight to attack microplastic particles near the glass surface. The overall formulation strategy from composition to functionality is summarised in Fig. 2, highlighting the role of each component in enhancing mechanical strength, optical clarity, and self-cleaning performance.

Mechanism and Function

The self-cleaning mechanism of this glass relies on the photocatalytic activity of embedded ZnO nanoparticles. When exposed to UV or sunlight, ZnO absorbs photons and generates electron–hole pairs, which react with oxygen and moisture in the environment to produce reactive oxygen species (ROS). These ROS are capable of oxidizing and breaking down organic contaminants, including the polymers that constitute microplastic particles (Kołodziejczak-Radzimska & Jesionowski, 2014; Kumar & Devi, 2011).

Meanwhile, chitosan modifies the ionic packing within the glass, enhances hydrophilicity, and provides additional antimicrobial activity (Jena et al., 2023). Because both ZnO and chitosan are embedded within the bulk glass, the self-cleaning functionality is long-lasting and does not suffer from delamination or surface wear, common issues associated with surface-applied coatings.

Applications

The embedded chitosan–ZnO phosphate glass system is highly versatile and holds significant potential for various practical applications. In water purification systems, it can be integrated into filtration units or substrates to reduce microplastic contamination through active degradation, rather than relying solely on passive trapping (Eerkes-Medrano et al., 2015). In solar panels and architectural glass, its self-cleaning properties reduce maintenance requirements and enhance energy efficiency (Algradee et al., 2022).

In marine environments, this glass can be applied to submerged surfaces or equipment to minimise biofouling and plastic film accumulation. The comparative advantages of embedded self-cleaning glass over conventional surface-coated glass are illustrated in Fig. 3, demonstrating superior durability, extended activity lifespan, and improved environmental safety. From solar arrays and filtration membranes to underwater structures, this material shows promise for widespread and impactful deployment.

Sustainability Impact

This material innovation directly supports multiple Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including SDG 6 (Clean Water and Sanitation) and SDG 14 (Life Below Water) (Eerkes-Medrano et al., 2015). By integrating biodegradable and eco-safe materials such as chitosan, the glass reduces reliance on petroleum-based polymers and toxic additives (Islam et al., 2020; Jena et al., 2023). Its embedded design also aligns with SDG 12 (Responsible Consumption and Production), as the functionality is retained over time without the need for reapplication.

Because the self-cleaning effect is inherent to the material, it eliminates the need for additional chemical treatments, reduces maintenance requirements, and promotes a cleaner lifecycle overall. This represents a shift from conventional passive materials to proactive, environmentally intelligent systems.

References

-

Eerkes-Medrano, D., Thompson, R. C., & Aldridge, D. C. (2015). Microplastics in freshwater systems: A review. Water Research, 75, 63–82.

-

Farag, M. A., et al. (2022). Enhancement of optical properties in zinc phosphate glass nanocomposites. Journal of the Australian Ceramic Society, 58, 653–661.

-

Islam, M. M., Talukdar, S., Polymenis, M., & Patel, S. C. (2020). Chitosan-based bioactive materials in tissue engineering applications. Bioactive Materials, 5(1), 164–183.

-

Jena, K., et al. (2023). Physical, biochemical and antimicrobial characterization of chitosan prepared from tasar silkworm pupae waste. Environmental Technology & Innovation, 31, 103200.

-

Kołodziejczak-Radzimska, A., & Jesionowski, T. (2014). Zinc oxide—from synthesis to application: A review. Materials, 7(4), 2833–2881.

-

Algradee, M. A., et al. (2022). Evaluation of Nd³⁺-doped lithium-zinc phosphate glasses. Journal of Non-Crystalline Solids, 576, 121304.

-

Kumar, S. G., & Devi, L. G. (2011). Review on modified TiO₂ photocatalysis under UV/visible light: Mechanisms and insights. Journal of Physical Chemistry A, 115(46), 13211–13241.